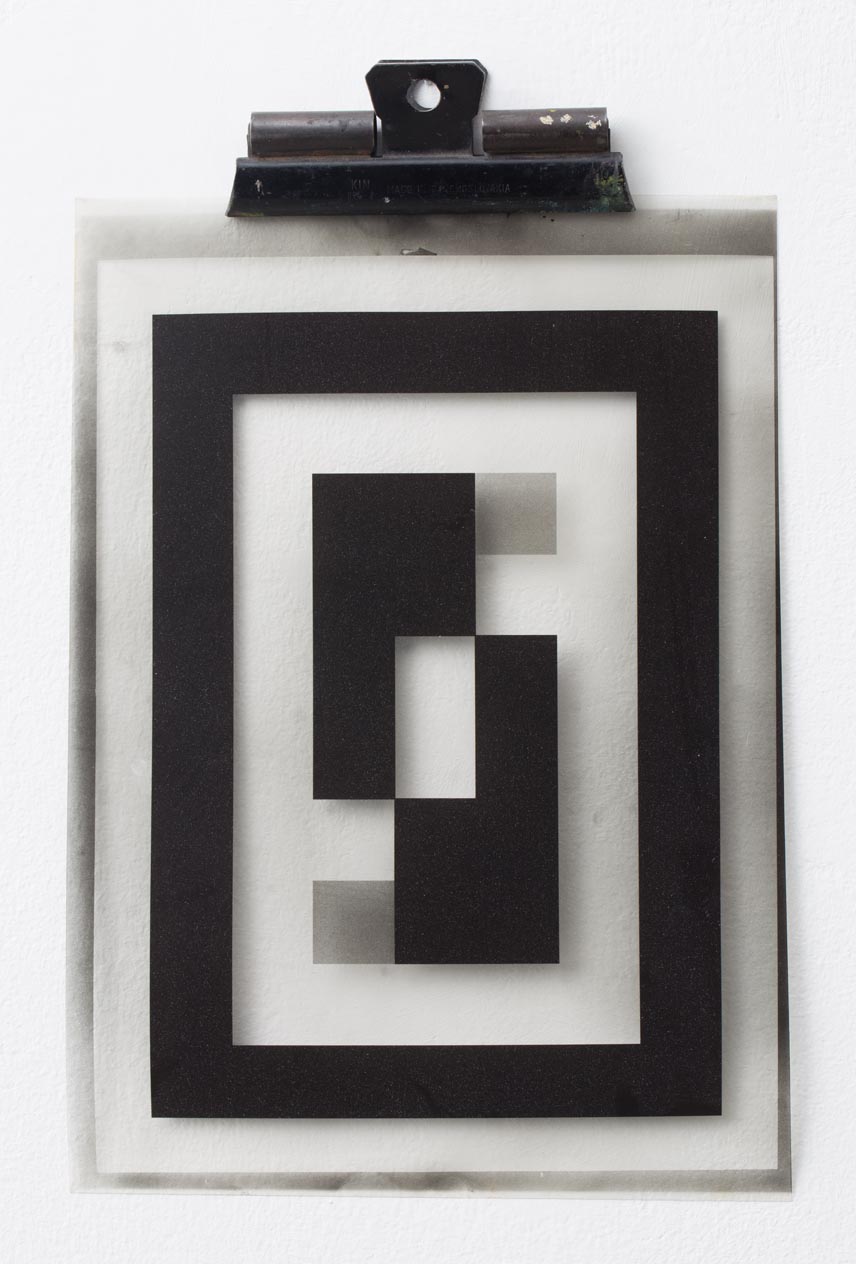

In recent years, Little Warsaw has undertaken a manifold investigation of the art object as a complex structure of codes, conventions and signifiers in a conversation between artists and the public. Their most recent work is a result of this exploration of analytical nature. Drawing on studies undertaken by the Bauhaus, and reinterpreting structuralist theories, they deconstruct the art object into its most basic elements: form, colour, and material. They create colour schemes made out of hand-painted plaster mosaic-cubes, geometric forms resembling educational tools, and patterns evolving around the concept of interchangeability. But their practice goes far beyond these minimalistic gestures: the artists also incorporate everyday objects – pieces of furniture, or ordinary objects like post-boxes – into their investigation, turning them into patterns and forms, discovering the very structures that constitute an artwork. Through a large variety of objects produced in this manner, Little Warsaw challenges the notions associated with art production, questions the traditional formats of display, and undermines our understanding of art as a visual language.

Katalin Székely

photography by Miklós Sulyok